The Lewis Turning Point

May 8, 2013

The Lewis model

The Lewis model

On my flight back to Nagoya, the city between Tokyo and Osaka, I grabbed a Chinese magazine written in English in an airport lounge at Pudon International airport. This magazine* describes today’s China by presenting numerous pictures, such as the recent Sichuan earthquake.

It was my first time to read this magazine and somewhat this magazine nicely killed my time on the two-hour flight back to Nagoya on NH940 from Shanghai. While reading through this magazine, I have found one economic vocabulary, the “Lewis turning point” on the page 43.

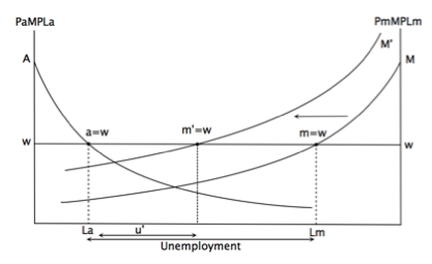

The Lewis model explains the supply of both agricultural and manufacturing labors at a certain wage level. In China, more than 70 percent of labor force was in the agricultural sector back in the 1980. Since then, its massive agricultural labor force has shifted into the manufacturing sector, which were mostly based in the coastal cities, such as Shanghai.

In the article, it is said that the labor shortage would become a hot topic. The supply curve of the manufacturing labor has significantly shifted to the left in the past decades at a certain wage level while the supply curve of the agricultural labor has also shifted to the left but less because the model assumes the certain wage level for the both labors (See the graph).

Therefore, the unemployed labor has gradually shrunken over the past decades and the model created the labor shortage. In addition, this model lacks the labor supply in the growing service sector, which tends to offer much higher wages. If there was another supply curve in it, it would describe a clear picture of the labor shortage. Plus, the service sector tends to hire skilled labor and this skilled labor is relatively limited; thus, it also creates labor shortage in the service sector.

Then, who can feed the Chinese while the agricultural labor force continues to diminish? The manufacturing labor, I believe, cannot produce food. I do not think the Chinese can eat steels or financial products. In order to obtain food for more than 1.3 billion of population, China needs to import food from other neighboring countries or increase productivity in the agricultural sector to produce more food.

On the other hand, the labor shortage at least creates employment for everyone but the wage increase highly depends on the productivity. According to the Cobb-Douglas form of production function, which I always like to utilize for topics in developmental economics, an increase in efficiency or some economists call it as TFP (Total Factor Productivity) can lead to much higher standard of living; thus, higher income.

The efficiency comes from technological advance, better political condition, rational behavior, and quality education. China needs to improve the efficiency to overcome the labor shortage, if it is true, or greater efficiency can promote more skilled labor to the service sector. Eventually it would also promote better air quality, clean food, and political condition.

* China Pictorial – A Window to the Nation A Welcome to the World, Vol. 799, May 2013

It was my first time to read this magazine and somewhat this magazine nicely killed my time on the two-hour flight back to Nagoya on NH940 from Shanghai. While reading through this magazine, I have found one economic vocabulary, the “Lewis turning point” on the page 43.

The Lewis model explains the supply of both agricultural and manufacturing labors at a certain wage level. In China, more than 70 percent of labor force was in the agricultural sector back in the 1980. Since then, its massive agricultural labor force has shifted into the manufacturing sector, which were mostly based in the coastal cities, such as Shanghai.

In the article, it is said that the labor shortage would become a hot topic. The supply curve of the manufacturing labor has significantly shifted to the left in the past decades at a certain wage level while the supply curve of the agricultural labor has also shifted to the left but less because the model assumes the certain wage level for the both labors (See the graph).

Therefore, the unemployed labor has gradually shrunken over the past decades and the model created the labor shortage. In addition, this model lacks the labor supply in the growing service sector, which tends to offer much higher wages. If there was another supply curve in it, it would describe a clear picture of the labor shortage. Plus, the service sector tends to hire skilled labor and this skilled labor is relatively limited; thus, it also creates labor shortage in the service sector.

Then, who can feed the Chinese while the agricultural labor force continues to diminish? The manufacturing labor, I believe, cannot produce food. I do not think the Chinese can eat steels or financial products. In order to obtain food for more than 1.3 billion of population, China needs to import food from other neighboring countries or increase productivity in the agricultural sector to produce more food.

On the other hand, the labor shortage at least creates employment for everyone but the wage increase highly depends on the productivity. According to the Cobb-Douglas form of production function, which I always like to utilize for topics in developmental economics, an increase in efficiency or some economists call it as TFP (Total Factor Productivity) can lead to much higher standard of living; thus, higher income.

The efficiency comes from technological advance, better political condition, rational behavior, and quality education. China needs to improve the efficiency to overcome the labor shortage, if it is true, or greater efficiency can promote more skilled labor to the service sector. Eventually it would also promote better air quality, clean food, and political condition.

* China Pictorial – A Window to the Nation A Welcome to the World, Vol. 799, May 2013