What is Middle-Income Trap?

January 27, 2015 (Originally written August 20, 2013)

Akira Kondo

A study of a middle-income trap has become enormously popular as China, the second largest economy across the globe, starts to show a sign of its weakening economy. Within a past few years, there have been many articles about the middle-income trap that were published from the international institutions, like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank as well as from international periodicals, such as The Economist and TIME. Academically, well-known professors, such as Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs, have published the middle-income-related articles. Interestingly, all of those publications are connected to today’s Chinese economy. “Can China escape from the middle-income trap” has become an intriguing question among economists. As more empirical evidence starts to back up this middle-income trap study, many economists have found out that middle-income countries need to move up the technological ladder in order to get out of the trap. This article reviews some recent literatures about the middle-income trap and find out the causes of the trap as well as basic solutions to avoid the trap.

Introduction

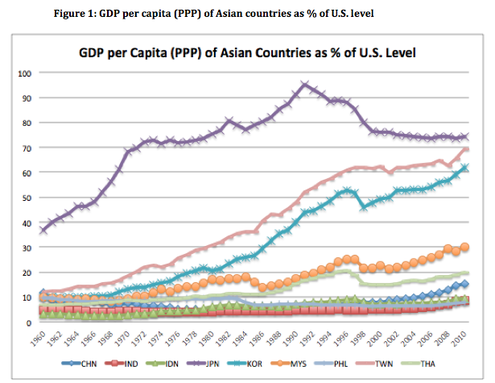

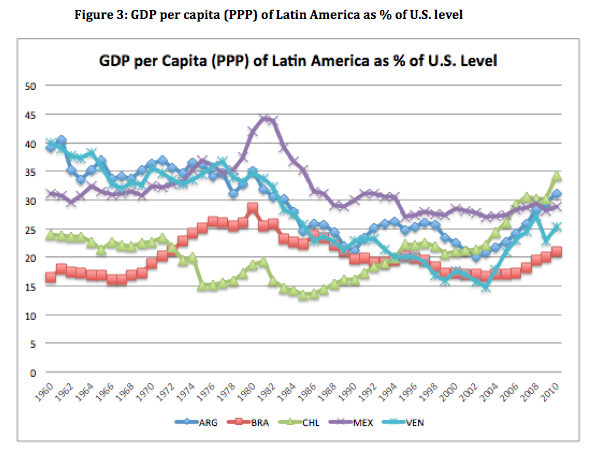

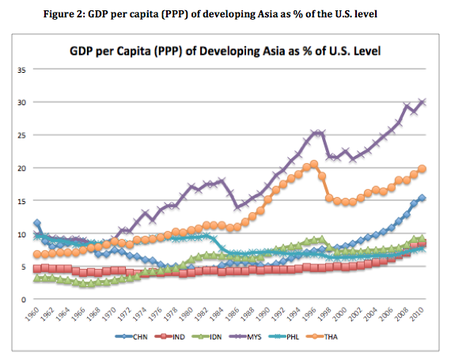

While the Asian region has presented the dynamic economic growth in the past, only few of the names have become the richer economies, namely Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. The other names all have remained in the middle-income status. According to Woo (2013), per capita GDP of the middle-income countries lie between 20 and 55 percent of that of the U.S. level, which is commonly accepted to have been the economic leader of the world at least since 1920. This ratio of a country’s income level to the U.S. income level is called, “Catch-Up Index (CUI).” Figure 1 represents how Japan, Korea, and Taiwan have experienced the greater convergence to the U.S. income level over the past years. Japan, for instance, its per capita level topped closed to the U.S. level in 1989 right before Japan’s bubble economy busted. The developing Asian countries in Figure 2 clearly express Malaysia is leading the race to get out of the middle-income level followed by Thailand and China. On the other hand, there are some exceptions that some countries in Latin America, which are shown in Figure 3, are diverging away from the U.S. income level. For instance, per capita income of Venezuela is now below the level of Malaysia while it was much higher than Malaysia in 1960. It is possible that some Asian middle-income countries someday are no longer able to catch up with higher income level countries while they may remain trapped in the middle-income level.

While the Asian region has presented the dynamic economic growth in the past, only few of the names have become the richer economies, namely Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. The other names all have remained in the middle-income status. According to Woo (2013), per capita GDP of the middle-income countries lie between 20 and 55 percent of that of the U.S. level, which is commonly accepted to have been the economic leader of the world at least since 1920. This ratio of a country’s income level to the U.S. income level is called, “Catch-Up Index (CUI).” Figure 1 represents how Japan, Korea, and Taiwan have experienced the greater convergence to the U.S. income level over the past years. Japan, for instance, its per capita level topped closed to the U.S. level in 1989 right before Japan’s bubble economy busted. The developing Asian countries in Figure 2 clearly express Malaysia is leading the race to get out of the middle-income level followed by Thailand and China. On the other hand, there are some exceptions that some countries in Latin America, which are shown in Figure 3, are diverging away from the U.S. income level. For instance, per capita income of Venezuela is now below the level of Malaysia while it was much higher than Malaysia in 1960. It is possible that some Asian middle-income countries someday are no longer able to catch up with higher income level countries while they may remain trapped in the middle-income level.

Therefore, what the CUI tells all about is the growth rate among countries in the relative term. In order to facilitate the faster economic growth for middle-income countries, they need to increase “efficiency,” which includes technological advance, education, social stability, and so on. Solow model clearly depicts that an increase in saving rate can only lead to a higher capital-intensity, which is unavoidable to diminishing returns to capital. However, an increase in the efficiency, such as technological development, can lead to a much higher steady-state equilibrium point without being an investment-driven economy. Countries that can move up the technological ladder may have more chance of getting out of the middle-income trap.

When looking at a country-specific case, China may become or have become a candidate of the middle-income trap country. Interestingly, many middle-income trap-related articles were published throughout past years and most articles have pointed out China’s possible trap in the middle-income level. Academically, well-known professors, such as Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs, published the middle-income trap articles this year. Two worldwide institutions, the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, have issued publications about China associated with the middle-income trap in 2011 and 2013, respectively. International periodicals, such as the Economist and TIME, also wrote articles about middle-income trap.